Learning to Generalize Kinematic Models to Novel Objects

Ben Abbatematteo

November 4, 2019

Objects with articulated parts are ubiquitous in household tasks. Putting items in a drawer, opening a door, and retrieving a frosty beverage from a refrigerator are just a few examples of the tasks we’d like our domestic robots to be capable of. However, this is a difficult problem for today’s robots: refrigerators, for example, come in different shapes, sizes, and colors, are in different locations, etc, so control policies trained on individual objects do not readily generalize to new instances of the same class.

Humans, on the other hand, learn to manipulate household objects with remarkable efficiency. As a child, we learn to interact with our refrigerator, then readily manipulate the refrigerators we encounter in the houses of our friends and relatives. This is because humans recognize the underlying task structure: these objects almost always consist of the same kinds of parts, despite looking a bit different each time. In order for our robots to achieve generalizable manipulation, they require similar priors. This post details our recent work towards this end, training robots to generalize kinematic models to novel objects. After identifying kinematic structures for many examples of an object class, our model learns to predict kinematic model parameters, articulated pose, and object geometry for novel instances of that class, ultimately enabling manipulation from only a handful of observations of a static object.

Kinematic Models

Kinematic models are commonly used to represent the relative motion of two rigid bodies. In particular, they describe a body’s forward kinematics: the position and orientation of an articulated part as a function of the state of a joint (the angle of a door or the displacement of a drawer, for example). The most common model types are revolute (like a door) or prismatic (like a drawer), but others exist as well (rigid, spherical, screw, etc). These models are parameterized by their position and orientation in space; for example, in the revolute model, the parameters consist of a) the axis about which the door rotates and b) the spatial relationship between the axis and the origin of the door.

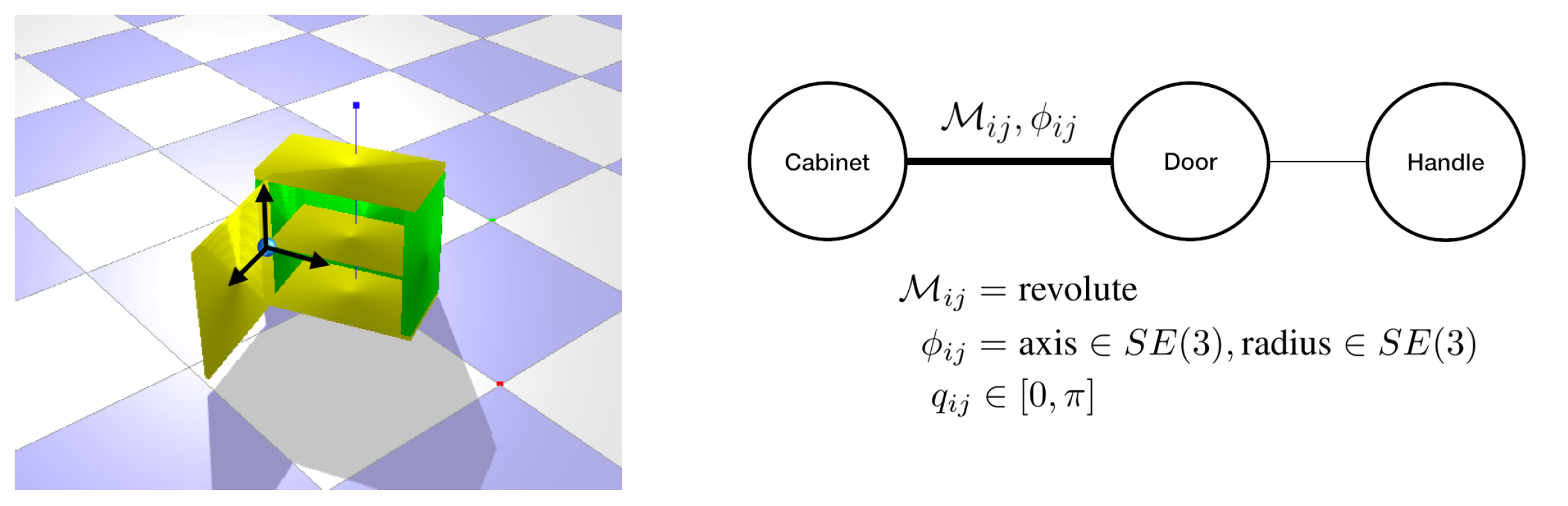

A kinematic graph represents all of an object’s parts and the kinematic models between them. Nodes in the graph represent the object’s parts, and edges encode model types and model parameters. For example, in Figure 1, the cabinet pictured can be abstracted into three nodes and two edges, with the rotation between the body and the door encoded in the edge between the respective parts.

Figure 1: An example object and its corresponding kinematic graph, annotated with the pose of the axis of rotation.

Figure 1: An example object and its corresponding kinematic graph, annotated with the pose of the axis of rotation.

To summarize, each node in the graph represents a part, and each edge in the graph consists of:

- Model type, denoted , between a part and its parent (revolute, prismatic, …) .

- Kinematic model parameters, , the axis of rotation/translation and the resting pose of that part.

- The state (or configuration) of the joint, denoted , an angle in revolute models and a displacement in prismatic models.

These quantities enable the robot to simulate how the object parts move about each other. If a robot can identify them, it can begin to reason about how to manipulate an object.

A large body of literature explores fitting kinematic models to individual objects, requiring part motion generated by either a human demonstrator or by the robot itself. Critically, these approaches fit models to each object from scratch: a demonstration is required for every new object, no matter how similar each is to those experienced previously. This results in a robot which has to deliberately explore every object it encounters, without ever learning the underlying structure in its experiences with those objects. This is insufficient for a robot operating autonomously in a new household environment, where every object it sees will be new.

Generalizing to New Objects

In contrast, our models are trained to predict kinematic model parameters from observations of static objects, providing the agent with a useful prior over a novel object’s articulation. We choose to categorize objects according to their part connectivity; once we do so, if our agent can recognize objects, it can identify the kinematic graph structure which represents a novel object. In particular, it will have the same connectivity as all other instances of that class. This enables us to define a template for each object class, then train neural network models which regress from depth images to the parameters of the kinematic model between each pair of parts, as well as the state of each of the object’s joints and a simple parameterization of the object’s geometry. After being trained in simulation, the models are capable of predicting kinematic model parameters for real, novel objects from individual observations. We show that this is sufficient for manipulating new instances of familiar object classes without first seeing a demonstration.

Model

The task of our neural network models is to predict the parameters of the kinematic model specified by the object’s class, , the object’s present articulated pose, , and a parameterization of the object’s geometry, , given the object’s class label, denoted , and a depth image of the object at time , . In order to enable the agent to express confidence in its estimates and reason about sequential observations in a principled way, we trained mixture density networks for each object class, which parameterize a mixture of Gaussian distributions over , , and . The mixture density networks consist of three neural networks, , , and , which represent the means, covariances, and weights of the mixture components, respectively. We trained ResNet backbones jointly with the mixture density networks. The resulting estimate of the joint distribution over model parameters, articulated pose, and object geometry has the following form:

In order to train the models, we require annotated depth images of articulated objects. Given the labels, the models are trained by maximizing the probability of the true labels under the parameterized mixture of gaussians:

Dataset

In the absence of an annotated collection of real articulated objects, we procedurally generated objects from geometric primitives, simulated them in Mujoco, rendered synthetic depth images, and recorded ground truth parameters. We did so for six object classes: cabinet, drawer, microwave, toaster oven, two-door cabinet, and refrigerator. Note that we need to classify cabinets into two categories according to the number of articulated parts due to our classification scheme described above. Ongoing work seeks to relax this by learning to identify part connectivity from pointclouds, too. Some samples from the dataset are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Sample simulated objects. The models are trained on many examples of a class, then tested on novel instances. Categories from the top: cabinet, drawer, microwave, toaster oven, cabinet2, refrigerator.

Manipulating Novel Objects

Once our models are trained, they enable a robot to estimate kinematic models for novel objects without first seeing demonstrations of their part mobility. Using an estimated kinematic model, after obtaining a grasp on the object, the agent is able to compute a path of its end-effector through space that sets the object’s degree of freedom to a desired setting while obeying the constraints imposed by the object’s joints. We demonstrated this with two real objects that the robot was not previously trained on: a microwave, and a drawer. Please see the video below for footage of the demonstrations.

Conclusion

It’s critical that a robot operating autonomously in new environments be capable of interacting with novel articulated objects. Existing approaches demonstrate how an agent might acquire a model of a novel object through exploration, but they fail to provide the agent with a useful prior over how the object might move. As such, the resulting exploration is time consuming and must be repeated from scratch for every object. Our work presented here provides a framework for learning to generalize these models to new objects, ultimately enabling zero-shot manipulation of novel instances of familiar object classes.

For more detail, see the paper, the code for the dataset, or the code for the model.