Learning Multi-Level Hierarchies with Hindsight

Andrew Levy

September 4, 2019

Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL) has the potential to accelerate learning in sequential decision making tasks like the inverted pendulum domain shown in Figure 1 where the agent needs to learn a sequence of joint torques to balance the pendulum. HRL methods can accelerate learning because they enable agents to break down a task that may require a relatively long sequence of decisions into a set of subtasks that only require short sequences of decisions. HRL methods enable agents to decompose problems into simpler subproblems because HRL approaches train agents to learn multiple levels of policies that each specialize in making decisions at different time scales. Figure 1 shows an example of how hierarchy can shorten the lengths of the sequences of actions that an agent needs to learn. While a non-hierarchical agent (left side of Figure 1) must learn the full sequence of joint torques needed to swing up and balance the pole, a task that is often prohibitively difficult to learn, the 2-level agent (right side of Figure 1) only needs to learn relatively short sequences. The high-level of the agent only needs to learn a sequence of subgoals (purple cubes) to achieve the task goal (yellow cube), and the low-level of the agent only needs to learn the sequences of joint torques to achieve each subgoal.

Figure 1: Video compares the actions sequences that need to be learned by a non-hierarchical agent (left) and a 2-level hierarchical agent (right) in order to complete the task. While the non-hierarchical agent needs to learn the full sequence of joint torques that move the agent from its initial state to the goal state (i.e., yellow cube), the 2-level agent only needs to learn relatively short sequences of decisions. The high-level of the agent just needs to learn the short sequence of subgoals (i.e., purple cubes) needed to achieve the goal. The low-level only needs to learn the short sequences of joint torques needed to achieve each subgoal (i.e., purple cube).

Yet, in order for hierarchical agents to take advantage of these short decision sequences and realize the potential of faster learning, hierarchical agents need to be able to learn their multiple levels of policies in parallel. That is, at the same time one level in the hierarchy is learning the sequence of subtasks needed to solve a task, the level below should be learning the sequence of shorter time scale actions needed to solve each subtask. The alternative is to learn the hierarchy of policies one level at a time in a bottom-up fashion, but this strategy both may forfeit the sample efficiency gains hierarchy offers and can be difficult to implement. Learning multiple levels of policies in parallel, however, is hard because it is inherently unstable. Changes in a policy at one level of the hierarchy may cause changes in the transition and reward functions at higher levels in the hierarchy, making it difficult to jointly learn multiple levels of policies.

In this post, we present a new Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning framework, Hierarchical Actor-Critic (HAC), that enables hierarchical agents to efficiently learn multiple levels of policies in parallel. The main idea behind HAC is to train each level of the hierarchy independently of the lower levels by training each level as if the lower levels are already optimal. This strategy yields stable transition and reward functions at all levels and thus makes it easier to learn multiple levels of policies simultaneously. The HAC framework is able to simulate optimal lower level policy hierarchies as a result of two components: (i) a particular hierarchical policy architecture and (ii) three types of transitions that take advantage of hindsight. Our empirical results in a variety of discrete and continuous domains show that hierarchical agents trained with HAC can learn tasks significantly faster than both non-hierarchical agents and hierarchical agents trained with another leading HRL approach. Further, to the best of our knowledge, our results include the first 3-level agents trained in tasks with continuous state and action spaces.

The remainder of the post is structured as follows. In the first section, we describe in more detail the instability issues that arise when agents try to learn to make decisions at multiple time scales. In the second section, we present our HRL framework and show how it can reduce this instability and thereby help agents to learn multiple levels of policies simultaneously. In the third section, we discuss the experiments we implemented and the results obtained. In final section of the post, we provide some concluding remarks. For a more detailed description of our approach and experiments, please see our ICLR 2019 paper. For open-sourced software to implement our framework, please check out our GitHub repository. In addition, for the video presentation of our experiments, please see the following video.

Instability in Hierarchical RL

Learning multiple levels of policies simultaneously is problematic due to non-stationary transition and reward functions that naturally emerge. Hierarchical policies almost always use some sort of nested structure. Beginning with the top level, each level will propose a temporally extended action and the level below has a certain number of attempts to try to execute that temporally extended action. Thus, for any temporally extended action from any level above the base level, the next state that action results in and potentially the reward of that action depend on the policies below that level. As a result, when all levels in the hierarchy are learned simultaneously, the transition function and potentially the reward function for any level above the base level may continue to change as long as the policies below that level continue to change.

For an example of non-stationary transition functions in hierarchical policies, consider the 2-level toy robot in the video in Figure 2 below. The high-level of this agent attempts to break down the task by setting subgoals for the low-level to achieve. The video shows four different occasions in which the high-level of the agent proposes state B as a subgoal when the agent is currently in state A. Yet due to the nested structure of the 2-level agent, the next state that this high-level action results in after a certain number of attempts (in this case 5) by the low-level will depend on the policy of the low-level. But since the low-level should be improving and likely also exploring over time, the next state that this subgoal action results in will change over time.

| Iteration | State | Action | Next State |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | B | C |

| 2 | A | B | D |

| 3 | A | B | E |

| 4 | A | B | B |

Figure 2: Example of non-stationary transition functions that arise when learning hierarchical policies. In this example, when the robot proposes subgoal state B when in state A, the next state that this action results in changes over time as the low-level policy changes.

Similarly, non-stationary reward functions can also arise when trying to learning multiple levels of policies simultaneously. Figure 3 shows an example in which a 2-level robot proposes and achieves the same subgoal on two different occasions, but receives transitions with different rewards because the agent follows different paths to the subgoal.

| Iteration | State | Action | Reward | Next State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | B | -13 | B |

| 2 | A | B | -4 | B |

Figure 3: Example of non-stationary reward functions that arise when learning hierarchical policies. In this example, even though in both iterations the agent is able to achieve subgoal B, the low-level takes different paths so the same subgoal action may yield different rewards. In this case, the reward function is assumed to be -1 for any primitive action that does not achieve the goal of task (not shown) and 0 otherwise.

Non-stationary transition and reward functions are a significant concern because they make it difficult to learn effective policies. RL algorithms typically estimate the expected long-term value of action in state (i.e., ) as the sum of the immediate reward and the discounted value of the current policy in the succeeding state (i.e., ):

$$Q_{Target}(s_t, a_t) = r_{t+1} + \gamma V_{\pi}(s_{t+1}).$$

If and do not have stationary distributions for the same state-action pair, Q-values will not stabilize and it will be difficult to value individual actions, which in turn will make it difficult to learn effective policies. Thus, in order for the hierarchical agent to learn all of its policies in parallel and realize the sample efficiency benefits of HRL, the non-stationary transition and reward functions that occur at all levels above the base level will need to be overcome.

Hierarchical Actor-Critic (HAC)

The key problem described above is that if all of the levels of the hierarchy are to be trained in parallel, the temporally extended actions from any level cannot be evaluated with respect to the current hierarchy of policies below that level. This lower level hierarchy will continue to change as long as these lower level policies both learn from experience and explore. Changes in lower level policies in turn will cause non-stationary transitions and rewards functions at higher levels that will make it difficult to learn effective policies at those higher levels. The central idea of our approach, Hierarchical Actor-Critic (HAC), is that instead of evaluating the temporally extended actions with respect to the current lower level hierarchy of policies, evaluate the temporally extended actions with respect to where the lower level hierarchy is headed — an optimal lower level hierarchy. The optimal lower level hierarchy, which consists of optimal versions of all lower level policies, does not change over time. As a result, the distribution of succeeding states and rewards for any temporally extended action will be stable, enabling the hierarchical agent to learn its multiple levels of policies in parallel. Agents that learn with the HAC framework are able to train each non-base level of the hierarchy with respect to optimal versions of lower level policies without actually needing the optimal lower level policy hierarchy as a result of the framework’s two major components: (i) the particular architecture of the hierarchical policy HAC agents learn and (ii) three types of transitions that the agent uses to evaluate actions.

Hierarchical Policy Architecture

Agents trained with HAC learn hierarchical policies with the following structural properties.

-

Deterministic, Goal-Conditioned Policies

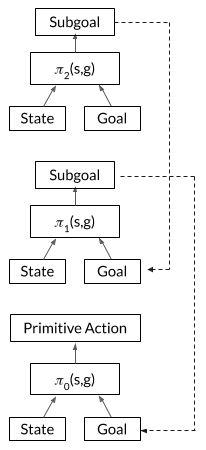

HAC agents learn -level hierarchical policies that consist of deterministic, goal-conditioned policies. The number of levels, , is a hyperparameter chosen by the user. Thus, at each level , the agent learns a policy that maps the current state and goal of the level to an action: . The goal will typically be an individual state or a set of states. The space of goals for the highest level of the hierarchy is determined by the user. The goals for all other levels are determined by the actions from the level above.

-

Action Space = State Space for Non-Base Levels

HAC agents divide tasks into shorter horizon subtasks using the state space. That is, each policy above the base level attempts to decompose the task of achieving its goal state into a short sequence subgoal states to achieve along the way. Setting the action space of the non-base levels of the hierarchy to be the state space is critical because it makes it simple for the agent to create transitions that simulate an optimal lower level policy hierarchy, which will ultimately help the agent learn multiple levels of policies in parallel. We will explain in more detail why this is the case during our discussion of the three types of transitions HAC agents use to evaluate actions. In addition, the action space for the base level of the hierarchy is the set of primitive actions available to the agent.

-

Nested Policies

The hierarchical policies learned by HAC agents are also nested in order to make it easier for higher levels in the hierarchy to learn to act at longer time scales. When a non-base level outputs a subgoal state, this subgoal is passed down to level as its next goal. Level then has at most attempts to achieve this goal state, in which is a hyperparameter set by the user.

Figure 4 shows the architecture of a 3-level agent trained with HAC.

Figure 4: Architecture of a 3-level hierarchical policy using HAC. Each of the three policies is deterministic and goal-conditioned as each policy takes an input the current state and goal state. The top two levels have an action space equal to the state space as these policies will output subgoal states for lower levels to achieve. The bottom level will output primitive actions. Further, each level has H actions to achieve its goal state before another goal is provided.

Three Types of Transitions

In addition to the structure of the hierarchical policy, HAC agents are able to efficiently learn multiple levels of policies simultaneously as a result of three types of transitions HAC agents use to evaluate actions. We describe each of these transitions next. In order to make these transitions easier to understand, we will make use of the example episode shown in Figure 5 below, in which a 2-level robot is trying to move from its initial state to the yellow flag.

Figure 5: Example episode of a 2-level agent trying to move from the initial state to the yellow flag. The pink circles with the label represent the original subgoal state proposed by the high-level of the agent at step The gray circles with the label indicate the state of the agent after primitive actions by the low-level policy following the proposal of subgoal

-

Hindsight Action Transitions

In order to efficiently learn multiple policies in parallel, the non-base levels of the hierarchy need transitions that evaluate actions as if the lower level policies are already optimal. This is the purpose of the first set of HAC transitions, which we refer to as hindsight action transitions. Hindsight action transitions are implemented using a simple procedure: replace the proposed action with the action that was actually executed in hindsight. For non-base levels of the agent that propose subgoals, this means that whenever a level proposes some subgoal state but the level below misses that subgoal state and ends in some other state after attempts, the hindsight action transition will use the state the agent ended in as the original subgoal action. With this change, the action and next state components in the transition will be the same and thus hindsight action transitions can simulate how an optimal lower level policy hierarchy would act. In addition, for the reward component of the transition, the reward will only depend on (i) the state reached after attempts and (ii) the goal state for the level in consideration. The reward will not take into consideration the exact path taken to the state reached after attempts because the goal is to create transitions that simulate an optimal lower level policy hierarchy and it is not known what path an optimal lower level policy hierarchy would take. The reward will also be sparse and binary to avoid the issues that arise when reward functions are manually engineered. Specifically, the reward for each level, will be 0 for any action in which and -1 otherwise.

Figure 6 shows the hindsight action transitions that would be created for the high-level of the agent in the example episode in Figure 5. Note that had the high-level had access to the optimal version of the low-level policy, the transition would look the same.

Iteration State Action Reward Next State Goal Discount Rate 1 s0 s1 -1 s1 Yellow Flag γ 2 s1 s2 -1 s2 Yellow Flag γ 3 s2 s3 -1 s3 Yellow Flag γ 4 s3 s4 -1 s4 Yellow Flag γ 5 s4 s5 -1 s5 Yellow Flag γ Figure 6: High-level hindsight action transitions created in the example episode shown in Figure 5.

For the low-level of the agent, the hindsight action transitions will be the typical transitions created for flat agents. -

Hindsight Goal Transitions

Although hindsight action transitions help hierarchical agents jointly learn multiple levels of policies by reducing the non-stationary transition and reward function issues, they introduce another problem — how to learn multiple levels of policies with only sparse reward functions. The HAC framework attempts to overcome this problem by supplementing agents with a second type of transition, which we refer to as hindsight goal transitions. Hindsight goal transitions make it easier to learn multiple level of policies in sparse reward settings by essentially extending the idea of Hindsight Experience Replay (HER) (Andrychowicz et al., 2017) to the hierarchical setting. HER helps agents learn to reach different goal states in sparse reward domains by generalizing from the agent’s experience achieving other goal states. HER is implemented by creating copies of the original transitions and replacing the original goal state with a state that was actually achieved during the episode. The original reward is also replaced with the appropriate reward given the new goal state. Hindsight goal transitions are implemented in the same manner as HER transitions except that in non-base levels of the hierarchy, hindsight goal transitions are made from copies of the hindsight action transitions.

Figure 7 lists the hindsight goal transitions created for the high-level after the example episode in Figure 5 assuming the last state that was reached, , is used as the new goal state. Figure 8 lists the hindsight goal transitions created for the low-level after the 5 attempts to try to achieve the first subgoal assuming the state is used as the new subgoal. Note that the last transition in these tables now includes the sparse reward of 0 and a discount rate of 0. Each level of the agent can now use this “knowledge” of how to reach these goal states to generalize to other goal states.

Iteration State Action Reward Next State Goal Discount Rate 1 s0 s1 -1 s1 s5 γ 2 s1 s2 -1 s2 s5 γ 3 s2 s3 -1 s3 s5 γ 4 s3 s4 -1 s4 s5 γ 5 s4 s5 0 s5 s5 0 Figure 7: High-level hindsight goal transitions created in the example episode shown in Figure 5.Iteration State Action Reward Next State Goal Discount Rate 1 s0 Joint Torques -1 1st Tick Mark s1 γ 2 1st Tick Mark Joint Torques -1 2nd Tick Mark s1 γ 3 2nd Tick Mark Joint Torques -1 3rd Tick Mark s1 γ 4 3rd Tick Mark Joint Torques -1 4th Tick Mark s1 γ 5 4th Tick Mark Joint Torques 0 s1 s1 0 Figure 8: Low-level hindsight goal transitions created when the low-level attempted to achieve the first subgoal. -

Subgoal Testing Transitions

Hindsight action and hindsight goal transitions help agents learning multiple levels of policies in parallel using only sparse reward functions, yet a significant problem still remains. These transitions only enable non-base levels to learn Q-values for subgoal states that can actually be achieved within steps by the level below. They ignore subgoal states that cannot be reached in actions. Ignoring a region of the subgoal action space is problematic because the critic function may assign relatively high Q-values to these actions, which may then incentivize the level’s policy to output these unrealistic subgoals. For discrete domains, HAC overcomes this issue with pessimistic Q-value initializations. For continuous domains, HAC supplements agents with a third type of transition, which we refer to as subgoal testing transitions.

Subgoal testing transitions help agents overcome this issue by penalizing subgoal actions that cannot be achieved with the current lower level policy hierarchy. Subgoal testing transitions are implemented as follows. After a non-base level proposes a subgoal, a certain fraction of the time that level will decide to test whether the policy hierarchy below that level can achieve the proposed subgoal. All lower levels then must greedily follow their policy and not add exploration noise. If the level below is not able to achieve the proposed subgoal in actions, the level that proposed the subgoal is penalized with a subgoal testing transition that contains some low reward value. In our experiments, we used a reward value of for this penalty. As an example of a subgoal testing transition, assume that when the 2-level robot in Figure 5 was in state , the high-level of the robot decided to test whether the low-level could achieve the proposed subgoal . The low-level policy then had to follow its policy exactly for steps. Because the low-level policy failed to achieve , the high-level would receive the subgoal testing transition below. Note that this transition uses a discount rate of 0 to avoid any non-stationary transition function issues.

Subgoal testing transitions thus help agents assign low Q-values to unrealistic subgoals because these subgoal actions will be penalized during subgoal testing.

Using these three types of transitions, the policy at each level of the hierarchy can then be trained with an off-policy Reinforcement Learning algorithm (e.g., Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) (Lillicrap et al., 2015)). The critic or Q-function at each level will take the form of a Universal Value Function Approximator (Schaul et al., 2015) that maps states, goals, and actions to the real number space: .

The hierarchical architecture and the three types of transitions constitute the bulk of the HAC framework. For the full HAC algorithm, please see our ICLR 2019 paper. For open-sourced software to implement our approach, please see our GitHub repository.

Experiments

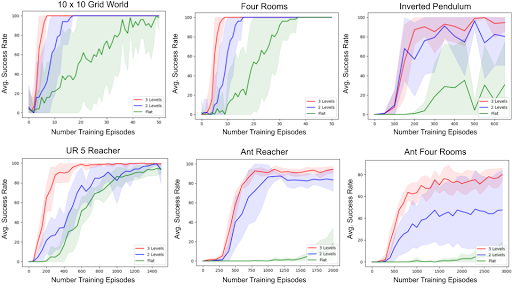

We evaluated our approach on both (i) discrete state and action space and (ii) continuous state and action space environments. The discrete tasks consisted on two grid world tasks: (i) 10x10 grid world and (ii) four rooms. The continuous domains consisted of the following four tasks built in MuJoCo (Todorov et al., 2012): (i) inverted pendulum, (ii) UR5 reacher, (iii) ant reacher, and (iv) ant four rooms.

Using these environments, we performed two comparisons. The first comparison we implemented compared agents using 1 (i.e., flat), 2, and 3 levels. The purpose of this comparison was to evaluate our hypothesis that HAC agents with more levels of hierarchy could learn new tasks with better sample efficiency as they can divide tasks into shorter horizon subtasks and solve these simpler subtasks in parallel. In this experiment, the flat agents used Q-Learning + HER in the discrete tasks and DDPG + HER in the continuous domains. Figure 9 below compares the performance of each agent type in all of the tasks listed above. The green, blue, and red lines represent the performance of 1, 2, and 3-level agents, respectively. In all tasks, hierarchical agents significantly outperformed the 1-level agents. Further, in all tasks, the 3-level agents outperformed, often significantly, the 2-level agents.

Below we show two short videos from our ant experiments. For the full video presentation showing all of our experiments, please see our YouTube video.

Figure 10: 2-Level HAC agent in the ant reacher task. The task goal is the yellow cube. Subgoal actions from the high-level policy are represented by the purple cubes. Low-level policy outputs joint torques.

Figure 11: 3-Level HAC agent in the ant four rooms task. The task goal is the yellow cube. Subgoal actions from the high-level and mid-level policies are represented by the green and purple cubes, respectively. Low-level policy outputs joint torques.

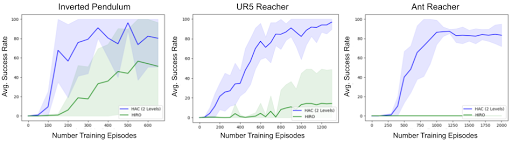

The second comparison we implemented compared HAC to another leading HRL algorithm, HIRO (HIerarchical Reinforcement learning with Off-policy correction) (Nachum et al, 2018). HIRO, which was developed simultaneously and independently to our approach, trains 2-level agents with a similar architecture to our approach and can also learn off-policy as in our approach. However, HIRO does not use either of our hindsight transitions, and therefore should not be able to learn multiple levels of policies in parallel as efficiently as our approach can. We compared 2-Level HAC with HIRO in the inverted pendulum, UR reacher, and ant reacher tasks. The results are shown in Figure 12 below. The green and blue lines represent the performance of HIRO and 2-Level HAC, respectively. In all tasks, 2-level HAC significantly outperforms HIRO.

Conclusion

Hierarchy has the potential to accelerate learning but in order to realize this potential, hierarchical agents need to be able to learn their multiple levels of policies in parallel. In this post, we present a new HRL framework that can efficiently learn multiple levels of policies simultaneously. HAC can overcome the instability issues that arise when agents try to learn to make decisions at multiple time scales because the framework primarily trains each level of the hierarchy as if the lower levels are already optimal. Our results in several discrete and continuous domains, which include the first 3-level agents in tasks with continuous state and action spaces, confirm that HAC can significantly improve sample efficiency.

Thank you Kate Saenko, George Konidaris, Robert Platt, and Ben Abbatematteo for your helpful feedback on this post.